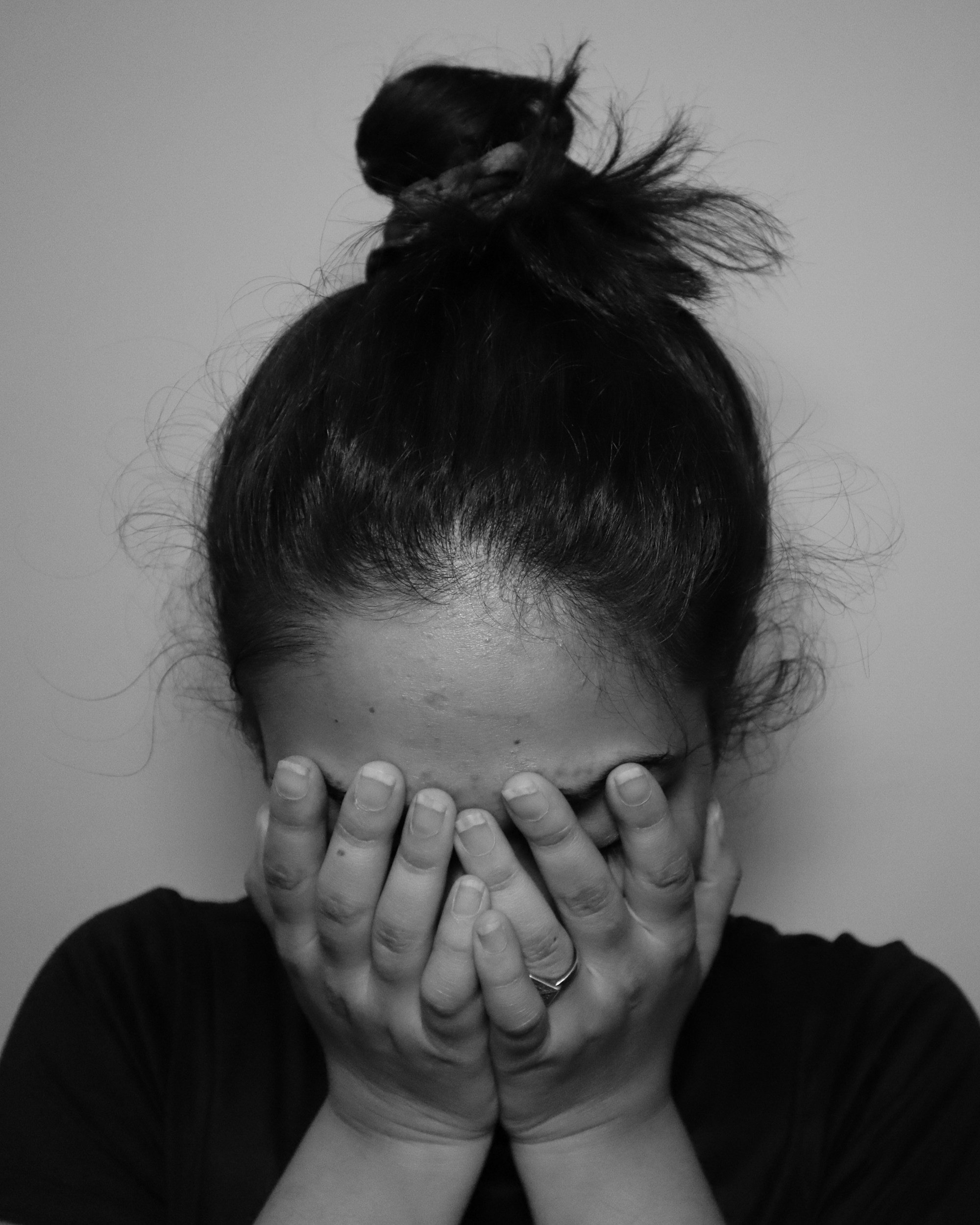

How the Hopelessness Epidemic is Taking the Workplace by Storm

Originally published in Fortune Magazine - Authored by Jennifer Moss and Jen Fisher

Hopelessness is at epidemic levels and taking a toll on people and organizations. Workers of all ages are feeling more hopeless than ever. A national poll released this past spring by the Institute of Politics at Harvard Kennedy School found that nearly half of Americans under 30 years old reported feeling “down, depressed, or hopeless” at least several days a week. In 2023, U.S. employee engagement fell at a rate 10 times faster than in the previous three years, according to one estimate. Globally, employee stress is at a record high, according to Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace 2023 report.

It has often been said that hope is not a strategy, but it’s time to challenge that myth. Hope is not only a powerful strategy to inspire change but also a key leadership skill for thriving in an uncertain future.

Hope, as defined in Snyder’s Theory of Hope, named for the late psychologist and researcher Charles Snyder, can be the antidote to uncertainty. Hope helps people envision a concrete path to a better situation, empowering them to set goals and make plans to reach these positive outcomes. It drives action, propelled by the will to follow through. It’s an attribute that is more tangible and goal-oriented than related emotions like optimism and empathy–and it’s those qualities that make it both possible and necessary to operationalize hope in the workplace.

A constant state of polycrisis

Yet hope has been hard to come by lately, and there are a few reasons why. As the pandemic moves into our rearview, the rapid adoption of new technology and AI is keeping uncertainty at the forefront. Gallup data shows that more workers fear that technology is making their jobs obsolete. That fear jumped by seven points since 2021 and has grown more in the past two years than at any time in Gallup’s trend since 2017.

Fear of technology aside, research finds that being exposed to persistent crises leads to feelings of hopelessness, cynicism, and aggression. We’re living in a polycrisis state–facing a global pandemic, two major wars, political and economic uncertainty, and an onslaught of natural disasters. Many people feel like the doom loop will never end. Then, when feelings of hopelessness persist, a 2023 study found that it decreases our sense of belonging, community, and performance. It also makes us susceptible to fight-or-flight responses, which increases emotional volatility.

We’ve all witnessed a dramatic rise in emotional instability since 2020. A New York Times article, aptly titled, A Nation on Hold Wants to Speak With a Manager, discusses the rise in “toxic customers” and their impact on professional cynicism and hopelessness. In 2020, there were 183 unruly airline passenger reports. In 2021, there were more than 5,981. One airline agent shared that before she would cry at this kind of treatment by a customer–now she’s just “judgmental” and “pessimistic.” This is just one of myriad sectors hit with enormous volatility. Customer experience, stakeholder relationships, innovation, and productivity are at risk if employees feel angry, stressed, and hopeless.

When it comes to retention, workers who describe feeling hopeless are more likely to miss work or disengage, leading to higher absenteeism and quit rates. And, hopelessness is contagious. Researchers have found that “one member’s pessimism and lack of motivation can influence others, diminishing team morale and cohesion.”

Hope is a hard skill

Hope has long had a reputation as a soft emotion, a Pollyanna perspective that everything will turn out just fine if you look at the bright side. But scientists are discovering that there is real power in hope. Higher levels of hope are connected to improved well-being and can help people find meaning and purpose. Hope builds resilience in the face of uncertainty–a key driver of workforce disengagement and attrition. Hope is an antidote to learned helplessness and makes people feel like they have the ability to address big, overwhelming problems. Hope also drives “human sustainability”–the degree to which an organization creates value for people as human beings, leaving them with greater health and well-being, stronger skills and employability, good jobs, opportunities for advancement, progress toward equity, increased belonging, and heightened connection to purpose.

The workforce has made a huge shift from empathetic to cynical over the last few years. If leaders care about employee well-being and the success of their firms, they must place rebuilding trust and hope at the top of their strategic agendas. Here are some practical suggestions for building hope skills for a future-ready workforce:

Reskilling and upskilling: To reduce fears of obsolescence, give workers the skills they need to meet future demand. Even if those skills aren’t applicable to your organization later on, they will increase worker hope today and ensure human sustainability for the future.

Be explicit when setting expectations: “Above and beyond” is not a concrete goal. We need to provide clear guidelines, ensure goals are attainable, and recognize and reward when key objectives are met.

Provide consistent but flexible feedback: Some workers like and need more frequent feedback, while others prefer less. Build flexible feedback systems that hit the right balance between under- and over-management

Embrace agency: People are more intrinsically motivated when they’ve been involved in defining and meeting their goals. If we want people to be more intrapreneurial and innovative while reducing learned helplessness, it’s critical to empower workers to solve problems in their own way.

Respect change fatigue: The workforce is still experiencing high rates of burnout which increases resistance to change. Ensure the change you’re making adds significant value right now–or let it wait. If change is imminent, exercise empathy. Ask people for open feedback throughout the process and act on what you hear to the best of your ability.

Celebrate when we deviate: When workers fail, let go of it quickly and reframe it as an opportunity for continuous learning. If workers feel like they have the psychological safety to try out new ideas without reproach, they will take more risks, which builds a cycle of hope.

Allow for recovery: Productive rest helps us to be more emotionally regulated and increases critical thinking. Never getting to the “bottom of the pile” increases a cycle of hopelessness. When workloads are unmanageable, people start to question the point of their efforts. They disengage. They’re less productive. And then their workload becomes even more unmanageable, creating a vicious cycle. Rest is a prerequisite for productivity. Leaders need to model the behavior so employees feel like rest is supported.

As more organizations begin to prioritize human sustainability by helping their employees become healthier, more skilled, and connected to a sense of purpose and belonging, they have an opportunity to instill hope in leadership and encourage it in workers.

An organization (or a community, or a family) filled with people that have a sense of meaning and purpose is stronger than one made up of disengaged, unhealthy, and unhappy people. Cultivating hope is an essential part of driving human sustainability. Organizations that embrace this perspective stand to build a virtuous cycle in which improving human outcomes enhances organizational outcomes and vice versa, contributing to a better future for all.

Jennifer Moss is an award-winning author, international speaker, and globally recognized workplace strategist. She is the author of, Unlocking Happiness at Work, The Burnout Epidemic, and her latest book, Why Are We Here, launches Dec. 3, 2024.

Jen Fisher is Deloitte’s U.S. human sustainability leader and a leading voice on the intersection of work, well-being, and purpose. She is the co-author of Work Better Together and the host of the WorkWell podcast series.